Otis House

Otis House

From Mansion to Medical Clinic

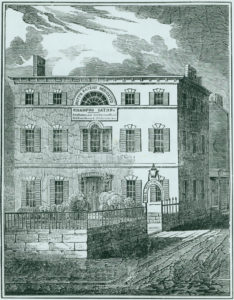

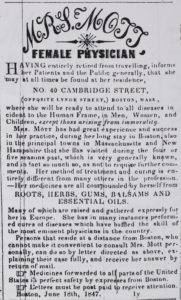

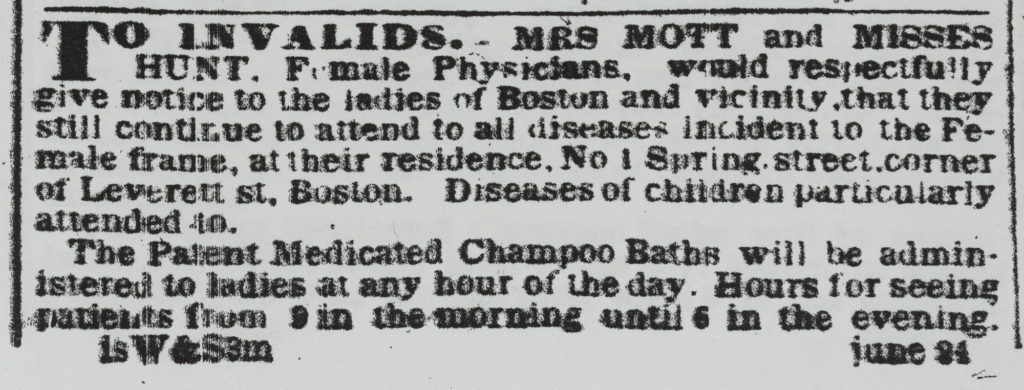

In 1822, the Otis House was divided into a two-family home, and sometime thereafter, single story shops were built into the front terrace. By 1834, Elizabeth Mott and her husband, Dr. Richard Mott had rented half the house to use both as their home and place of business. From the Otis House, Mrs. Mott offered free medical advice, sold over the counter remedies, such as Josephine’s dentifrice for whitening teeth, and treated patients with a “cure”, advertised as “Mott’s Patent Medicated Champoo Baths”.

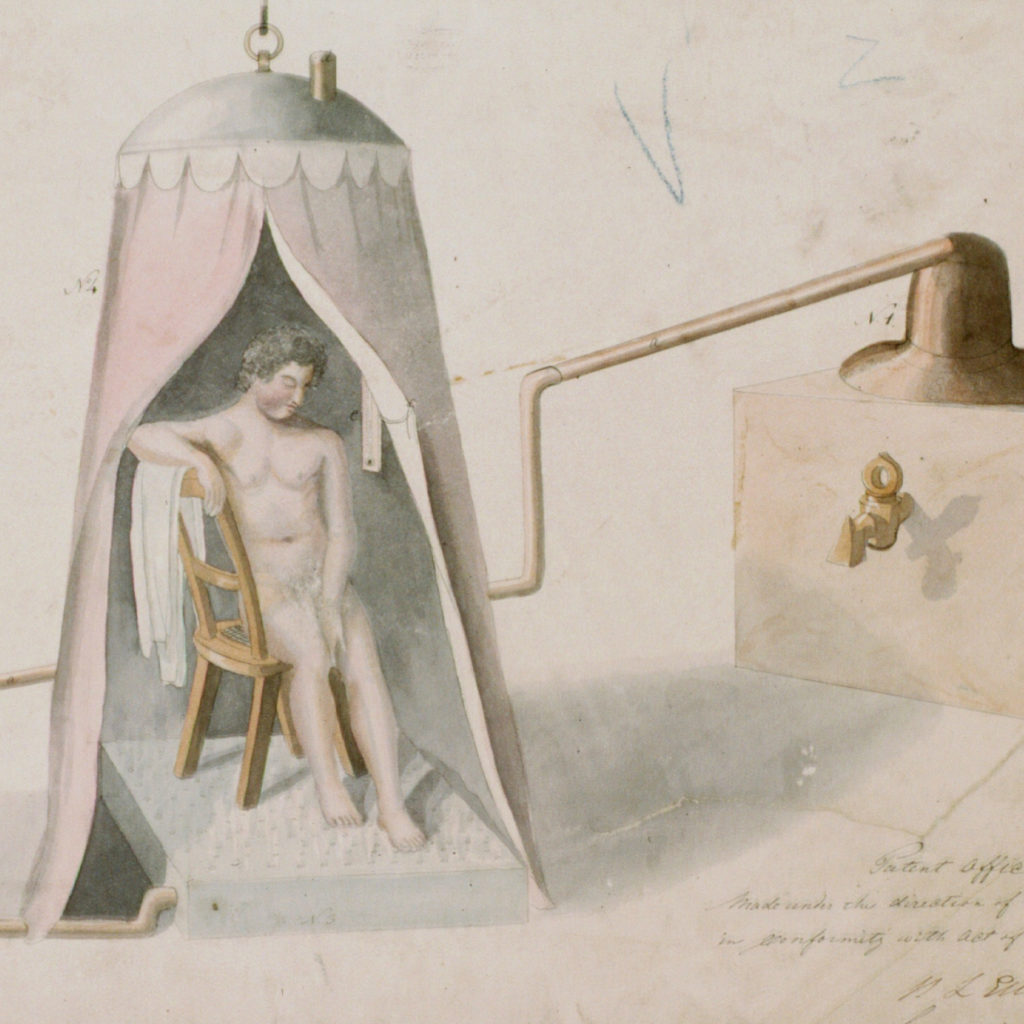

U.S. Patent Office Drawing

Mott's Patent Medicated Champoo BathPatent Drawing Champoo Bath

This patent drawing was submitted to the Patent Office in Washington D.C. in 1833 and shows how the steam bath worked. A patient would enter the chamber and sit inside the tent, with the sides pulled tight around him. Water was heated to a steam in the right hand tank and the steam traveled into the left hand tank through a pipe, where it mixed with essential oils, vegetable powders and herbs. Then medicated steam would then enter the tent where the patient was said to benefit from their healing properties as the steam seeped into their skin through the pores.

Elizabeth Mott

“the justly celebrated FEMALE PHYSICIAN of Boston”

Elizabeth Mott located herself at the matrix of traditional women’s healing and modern alternative medicine; her abilities, she argued, were the result of both a natural “gift” and careful study. For most of her career, Mrs. Mott limited her practice to women and children, arguing “ladies ought to have their own sex attend to them” because they could talk more openly with female doctors without violating standards of morality and modesty.

While popular with female patients (they claimed 4,000 patients in Boston), Mrs. Mott and her husband Richard, were not considered qualified doctors by the mainstream medical profession, which was taking hold in the neighborhood at the time. As urban neighborhoods can change dramatically, this neighborhood, the West End, was gradually changing from a residential neighborhood to a more commercial neighborhood with the founding of Massachusetts General Hospital in the 1820’s and increased traffic over the West Boston bridge.

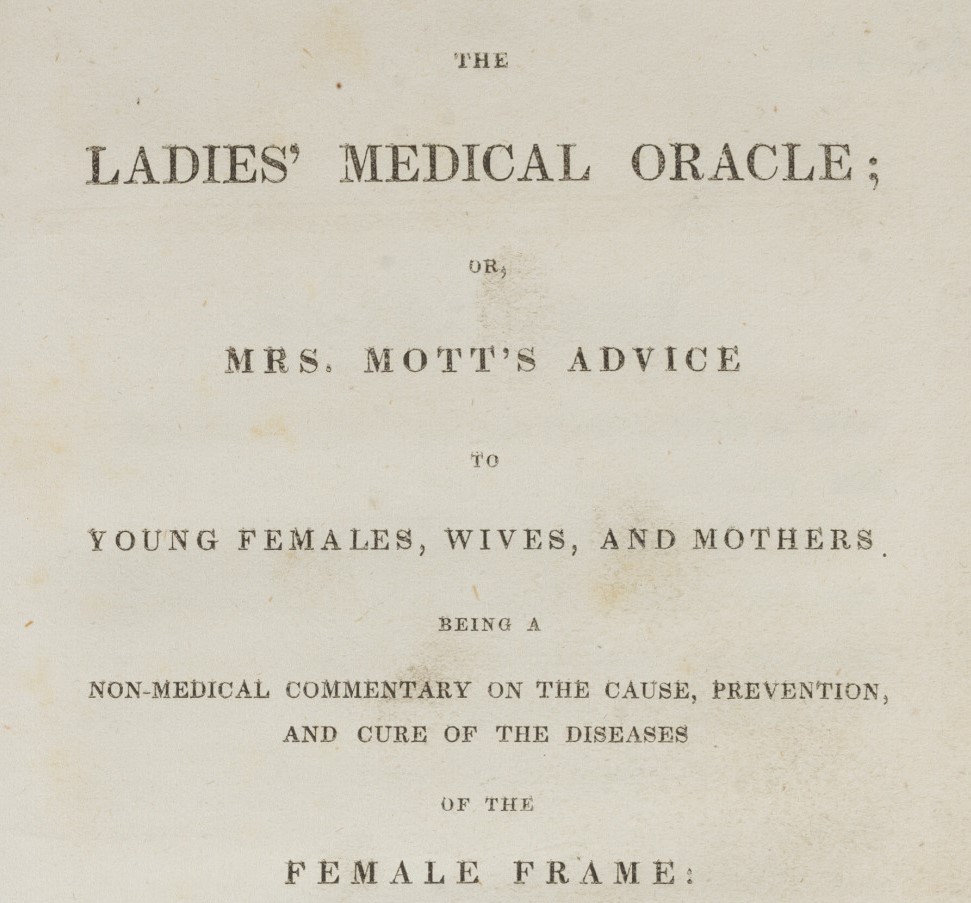

The Ladies Medical Oracle

Alternative Medicine in 1834

In 1834, Elizabeth Mott wrote a book, The Ladies Medical Oracle, which espoused her advice for women. She had many ideas that were rare for the time: she promoted loosening corsets, brushing teeth regularly, avoiding rich foods like butter, exercising, and incorporating the act of “shampooing,” which was a “remedy borrowed from Eastern nations.”

A few pieces of wisdom from Mrs. Mott’s book:

“It is not with doctors that I disagree, but with their complicated system of physic.”

“It may be necessary to state here, that my cures are made by simple applications of the vegetable world, and not by charms or witchery.”

“Although the body may be in perfect health, suffering of the mind must necessarily produce lassitude and dejection of spirits.”

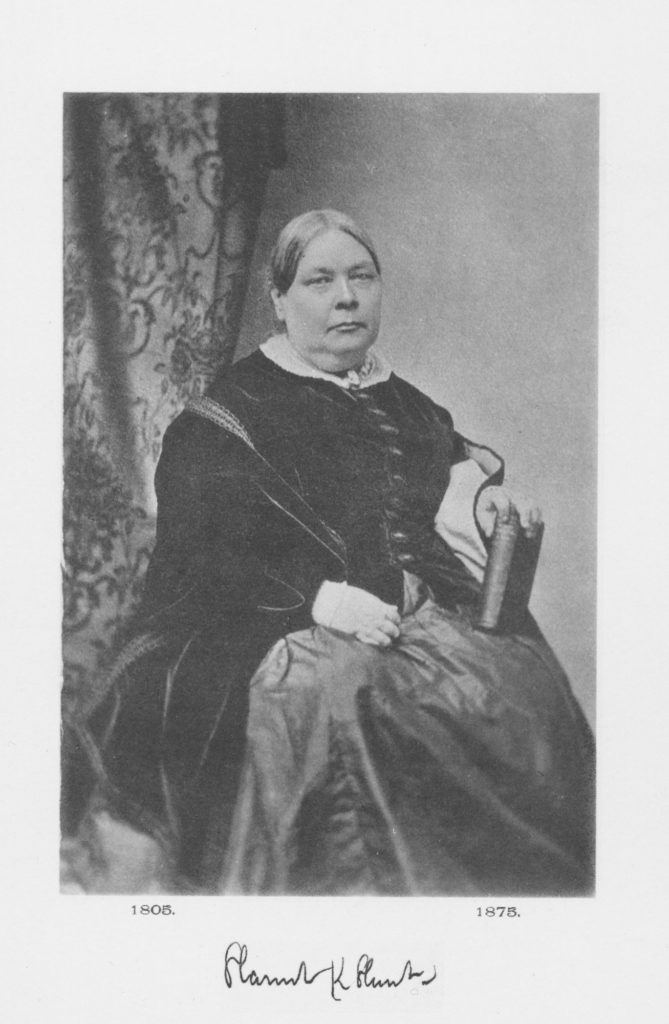

Harriet Hunt

Medical Pioneer

Harriot Hunt was a young teacher living in the North End when she came to see the Motts about her sister, who was ill. The Motts visited Harriot’s sister, and then asked Harriot to come work for them at their clinic in this house. Eventually, Harriot, her mother, and her sister all lived at the Otis House, in adjoining rooms .

The Motts apparently cured Harriot’s sister, and this inspired Harriot, to study medicine. She went on to become one of the first female physicians in the country. She was the first woman known to have applied to Harvard Medical School, a popular lecturer on women’s health issues, and a leader in women’s suffrage. She considered herself wedded to her profession and even wore a ring to symbolize her devotion. She often courted controversy by delivering public lectures designed to teach women about their own bodies.

A nineteenth century biography described Harriot Hunt’s career choice: “With no professional support…she launched from the safe harbor of domestic privacy and social protection upon an untried sea of responsibility and public scrutiny…” Harriet Hunt wrote an autobiography in 1856.