Otis House

Otis House

The West End

Mostly Gone, But Not Forgotten

Bounded by Beacon Hill on one side and the Charles River on another, Boston’s West End exists today as a faint memory of its fashionable residential and commercial beginnings. Throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth century, the neighborhood transitioned from the home of wealthy Bostonians to that of newly arrived Americans. This unique enclave of the city, along with its historic architecture and cultural richness, was all but obliterated between 1958 and 1960 in Boston’s post-World War II era urban renewal efforts.

Changes Over Time

Boston’s West End is part of the peninsula called Shawmut (the place of living fountains) by its Indigenous Native American inhabitants. In its earliest years of colonial settlement, it was quiet, undeveloped, and mostly pasture land. Considered the outskirts, or “urban fringe,” it was an area labeled as objectionable and undesirable, fit only for industry and institutional usage such as distilleries, copper-works, and gristmills.

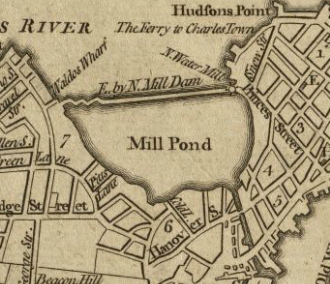

The Mill Pond

A Stagnant Body of Water Becomes an Early Landfill Project

At the northern end of the Shamut Peninsula, which would eventually become Boston’s North End, development first began in the seventeenth century with the construction of corn mills along the shore by a group of investors. The cove was dammed, a channel constructed, and floodgates built — all working in tandem to provide tidal water from the adjacent harbor to power the mills and, later, several rum distilleries.

But by 1800, garbage, refuse, and sewage made the Mill Pond area a notorious breeding ground for disease. Efforts to fill it were led by Harrison Gray Otis using a design by Charles Bulfinch, and much of the fill for the Pond came from the land taken from the top of Beacon Hill, having been excavated for the benefit of Otis and Bulfinch’s real estate development venture.

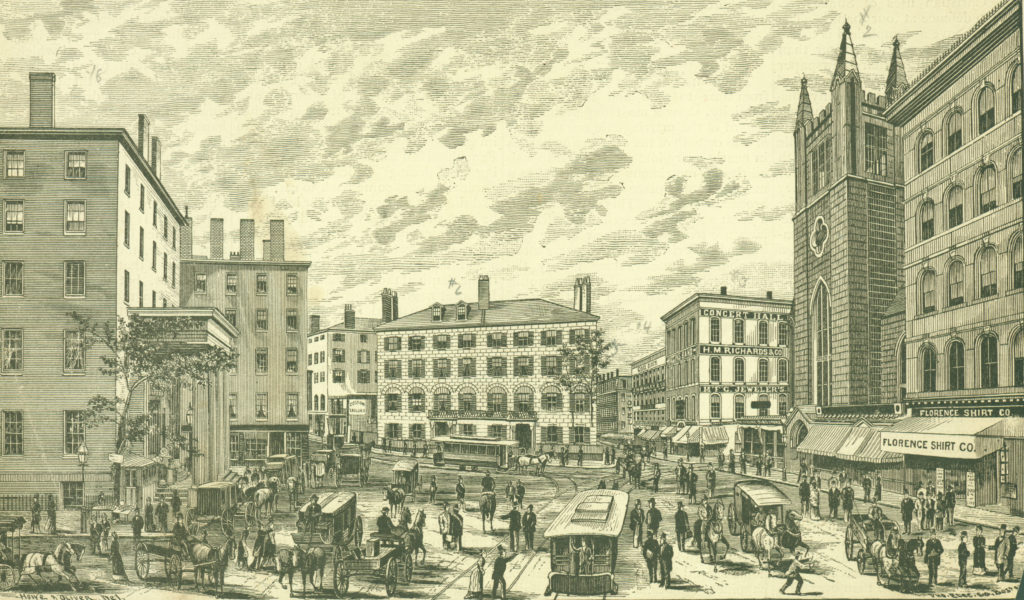

Bowdoin Square

What a Difference A Bridge Makes

Nestled in the West End, and originally called the “Bowling Green,” Bowdoin Square was quiet through most of the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. By the 1740’s the land in the West End closer to the city center had become more valuable for housing than agriculture. As the genteel population began to move from Boston’s urban center, Bowdoin Square became the fashionable home to family names such as Bulfinch, Otis, Parkman, and Gore. As the building of the Charles River and West Boston Bridges changed Cambridge Street into a busy main street, the character of the square changed as well, boasting markets, shops, businesses, and eventually street cars.

A Home Away From Home

The Rise and Fall of the Boarding House

By the middle of the nineteenth century, few Americans lived only with relatives throughout their lives; many people had boarders in their own homes, boarded with other people’s families, or lived in boarding houses. The rise in popularity of the boarding and lodging house was also fueled by immigration, the solution to a longstanding labor shortage. Arriving without places to live and with few household goods, newly-arrived immigrants often crowded into rooms, living in tenement-like conditions.

Boarding arrangements varied from household to household, and being that boarding was one of the only respectable means for women to earn income, most often the drudgery of running such an enterprise, such as making boarding arrangements, laundry, cooking, and cleaning, fell to women. In practice women often served as surrogate mothers, wives, and sisters for their borders, creating a sense of family.

In the later nineteenth century, the number of urban boarding houses declined, while lodging houses increased. Boarding house keepers found they could rent out the dining room and parlor as additional bedrooms and they could dismiss servants required to prepare and serve meals. In addition to paying a cheaper price, lodgers also found a more independent lifestyle; they could dine and socialize wherever and with whomever they chose.

Though people continue to live with friends or family for short periods of time, boarding has largely disappeared from the American lifestyle, and people who share houses and apartments today often simply share real estate.

Of Architects and Ether

The Growth of the Medical Community

Founded in 1799, trustee records indicate that Massachusetts General Hospital was chartered in 1811 and that by 1813 the search had begun to locate a suitable site for the fledgling institution. After considering sites at the foot of the Boston Common and another in Roxbury, a site in the West End was chosen in 1817 for its ability to provide the healthy benefits of good ventilation and natural light. The first MGH building was designed by architect Charles Bulfinch, and the operating theater, which had seating for observation beneath a sky-lit dome, became distinguished in 1856 as the place in which the first extensive surgical operation upon a patient under the influence of ether was successfully performed. By the mid-nineteenth century, the Harvard Medical School moved to North Grove Street in the West End, a new building to house the Massachusetts Charitable Eye and Ear Infirmary was erected at the corner of Charles and Cambridge Streets, and The Mount Sinai Hospital (later to become Beth Israel) was located on Chambers Street.

Row houses, 10-16 Lynde Street

Row houses, 10-16 Lynde Street

Numbers 14-16 are what remains of a series of four row houses on Lynde Street, tucked behind Otis House and currently used as office space for Historic New England and its tenants. Numbers 10-12 were razed when Otis House was moved back as part of a street improvement project. In 1925, the city of Boston began the widening of Cambridge Street, transforming it from a crooked cobblestoned street to a 100 foot wide thoroughfare intended to relieve congestion in the downtown area.

By 1900, 16 Lynde Street had made the transition from boarding to lodging house. The largest number of residents documented at 16 Lynde is twenty six in 1910. The head of the household was a French Canadian family of four. Of the remaining twenty two residents, eight were members of married couples (one of which had an infant). James and Patrick Walsh were probably brothers. One resident was born in Russia, one in English Canada, two in Ireland, and two in Italy.

Above: Numbers 14-16 Lynde Street, before Otis House is moved back but after 10-12 are razed, 1925.

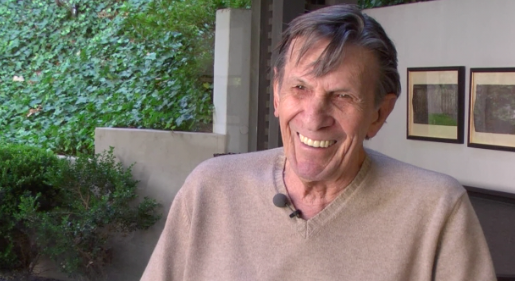

Leonard Nemoy's West End

View actor Leonard Nimoy’s memories of growing up in Boston’s West End: “A Village Life.” Courtesy of The Yiddish Book Center’s Wexler Oral History Project.