Otis House

Otis House

Beacon Hill

A Mountain of Change

Today, Beacon Hill is often thought of as an iconic Boston neighborhood, bounded by Beacon Street on the south, Bowdoin Street on the east, Charles Street on the west, and Cambridge Street on the north. But in its centuries of history lie the roots of Boston’s storied past, inhospitable slopes and pasturelands, Boston’s first real estate development, the building of a capital, and a diverse melting pot of both architecture and cultures.

How Did Beacon Hill Get Its Name?

A Defensive Signal System

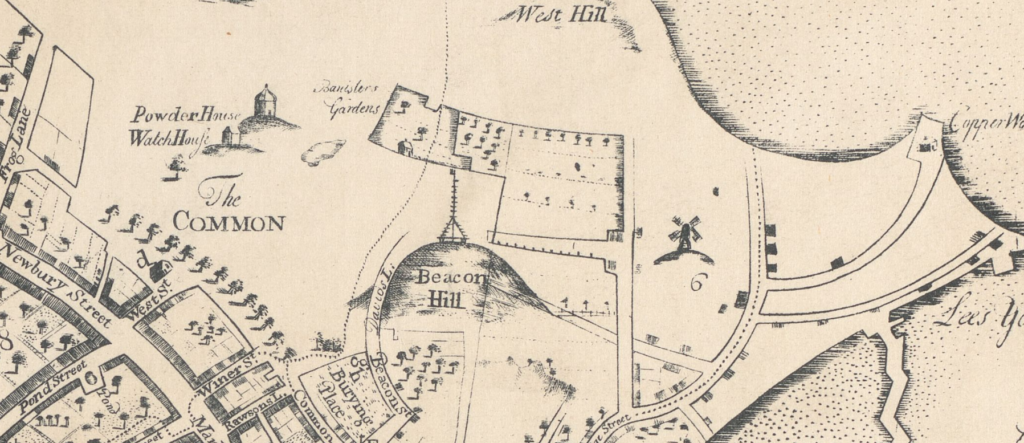

In 1634, the ruling General Court proclaimed that, “There shall be forthwith a beacon sett on the Centry Hill at Boston, to give notice to the country of any danger.” Rising sixty feet above the summit stood the beacon, a tall pole at the top of which was mounted an iron pot filled with combustibles. It was never lit, yet remained in place for a century and a half until 1789 when it blew down in a November storm.

Changes Over Time

The Beacon Hill of today offers little insight into its original habitat and dimensions. As portrayed in this nineteenth century romanticized painting by Samuel Lancaster Gerry, the peninsula was called Shawmut (the place of living fountains) by its Indigenous Native American inhabitants, and later described by early English settlers as “a mountain with three little hills rising on top of it” (or the Tri-mountain). As the predominant topographical feature of Boston’s early landscape, the hills known as Pemberton, Mt. Vernon, and the central summit, Beacon, offered a panoramic view of the harbor and surrounding countryside.

The Beacon Hill Proprietors

“We are taking down Mount Whoredom. If in future you visit it with less pleasure you will do so with more profit.” – Harrison Gray Otis

By the late eighteenth century, the northern slope of “Copley’s Hill” had become a small, isolated, rough-and-tumble community called West Boston. During the British occupation it was frequented by so many soldiers that it became known as “Mount Whoredom.” Beginning in 1799 the western summit of Beacon Hill had been shorn and laid out in house lots — the work of a real estate syndicate called the Mount Vernon Proprietors, originally made up of five prominent Bostonians: Harrison Gray Otis, Charles Bulfinch, Jonathan Mason, William Scollay, and Joseph Woodward. It later included others such as Hepzibah Swan, a woman of wealth who was developing prime properties on Chestnut Street. Ms. Swan’s participation was deemed “unofficial,” as women’s participation in such business endeavors were considered inappropriate at the time.

Perhaps one of the best known chapters of the association, which survived for almost thirty years, was the purchase of land owned by artist John Singleton Copley, who claimed that the Proprietors tricked him into selling his land at too low of a price. Copley initiated legal proceedings and tried to withdraw from the agreement, but the contract was ultimately declared binding and the Proprietors prevailed.

A Hill of Many Hues

Religious and Cultural Diversity

By 1790, the West End and the steep North Slope, initially settled by free Blacks in the 1760s, was becoming a thriving African American community. Residents sought to strengthen the community by building the African Meeting House on Joy Street.

By the mid-nineteenth century, Pinckney Street became the dividing line between the north and south slopes of the Hill. The North Slope neighborhood was penetrated by pedestrian alleys where lived a culturally diverse and racially mixed working class, many of them employed by the elite families living on the South Slope.

Epidemics, famine, and economic conditions in the Old World fueled the influx of new immigrants in the 1870s and 1880s and continued to transform Beacon Hill’s ethnic diversity. During this time, a large number of European Jews, as well as immigrants from Ireland, Italy, Greece, Syria, Latvia, and Jamaica fled to the United States and settled in this area of Boston.

Vilna Shul

Temple on the Mount

The Vilna Shul is the last remaining intact synagogue of its ear in Boston, and one of the last remaining links to the Jewish West End of the early twentieth century. With an original congregation made up of Jewish immigrants from Lithuania, the Vilna Shul had its heyday from 1920 through the 1950s, when the decline of Orthodoxy and the growth of Reformed and Conservative Judaism led the local congregation to move to other neighborhoods. Closing in 1985 with only one surviving member, the building sat idle until 1994, when it was rescued and transformed into the Vilna Shul/Boston’s Center for Jewish Culture, a destination and a place of learning for anyone interested in Jewish history, culture, and spirituality.

African Meeting House

Promoting Dignity and Respect for All

Designed by architect Asher Benjamin and built in 1806, The African Meeting House stands today as the oldest black church still standing in the United States. Prior to its construction, black Bostonians could attend white churches but generally faced discrimination, being forced to sit in segregated pews. The Meetinghouse became a place for celebrations and political and antislavery meetings for abolitionists. At the end of the nineteenth century, when the black community began to migrate to the South End of Boston, the building was sold to a Jewish congregation and remained a synagogue until it was purchased by the Museum of African American History in the 1970s and listed as a landmark on the National Register of Historic Places.

Beacon Hill Friends House

Spiritual Equality

The building that currently houses the Beacon Hill Friends House on Chestnut Street was designed by architect Charles Bulfinch in the early 1800s.

It was given to the Quakers in 1957 and established as an intentional Quaker community, and Quakers worship meetings began in the early 1960s. In 1980 Beacon Hill Friends Meeting, the fourth to meet in Boston, was officially incorporated as a separate meeting for worship with its own monthly meeting for business.

Charles Street Meeting House

"If there is no struggle, there is no progress." - Frederick Douglass

Designed by architect Asher Benjamin, the Charles Street Meeting House was built in 1807 to house the Third Baptist Church of Boston. The segregationist tradition of New England church seating patterns prevailed here, but were challenged in the 1830’s by church member Timothy Gilbert, paving the way for future speeches made here by prominent abolitionists such as Sojourner Truth, Wendell Phillips, Frederick Douglass, and Charles Sumner. The African Methodist Episcopal Church purchased the building in 1876, but by 1900 economic, social, and political forces made its continued existence on Charles Street difficult and the church moved to Roxbury in 1939. Today, the building houses four floors of offices, with retail on the ground floor. The exterior has been completely preserved.