Otis House

Otis House

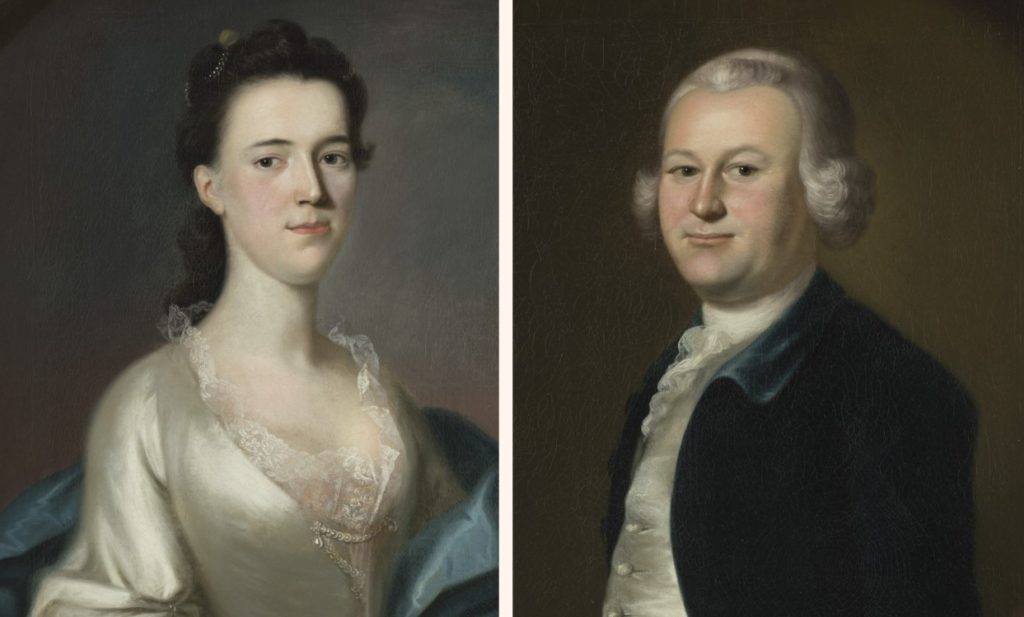

Sally Foster Otis

According to contemporary accounts, Sally Foster Otis (1770-1836) was described as “remarkable for beauty and wit as well as intellectual vivacity, tempered always by an indescribable grace.” Although Sally and her wealthy women contemporaries were part of a social whirl of high society parties they also worked very hard, leading busy strenuous lives that required them to juggle conflicting demands on their time and energies. Sally was the mother of eleven children, oversaw of a complex household that employed a staff of servants, and also managed Harrison’s business affairs when he was away in Congress.

Residents of Beacon Hill in 1796

Everyday LivesAt the time Otis House was built, most Bostonians were not living the elite and comfortable lifestyle that the Otises were enjoying. The following profiles are based on real people living on and around Beacon Hill in 1796 that were uncovered through the researching of public records.

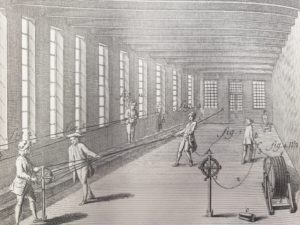

William Decruse was a thirty year veteran rope-worker who supplied Boston’s all-important shipping and fishing industry with this much needed resource, as each ship required hundreds of yards of rope for the sails, anchors, and other equipment on board. Because of this, Boston had many outdoor stretches of streets called “ropewalks,” including the one on which William worked, located on Myrtle Street on Beacon Hill’s North Slope. William had a reputation for sloppy work, but his wife, Sarah, was the sister of the foreman at the ropewalk, which kept him from being fired. The Decruse’s lived in two rooms of a large wooden house on Myrtle Street. They had no children of their own, but cared for two young orphans. To make rope, apprentices first started with small fibers from the hemp plant and twisted them together into long, thin strands of yarn. Rope-workers would then take the hemp yarn and twist several of the strands together to make the thinnest rope, called marline. Several of these thin marlines were then twisted together to make a heavier rope.

William Decruse was a thirty year veteran rope-worker who supplied Boston’s all-important shipping and fishing industry with this much needed resource, as each ship required hundreds of yards of rope for the sails, anchors, and other equipment on board. Because of this, Boston had many outdoor stretches of streets called “ropewalks,” including the one on which William worked, located on Myrtle Street on Beacon Hill’s North Slope. William had a reputation for sloppy work, but his wife, Sarah, was the sister of the foreman at the ropewalk, which kept him from being fired. The Decruse’s lived in two rooms of a large wooden house on Myrtle Street. They had no children of their own, but cared for two young orphans. To make rope, apprentices first started with small fibers from the hemp plant and twisted them together into long, thin strands of yarn. Rope-workers would then take the hemp yarn and twist several of the strands together to make the thinnest rope, called marline. Several of these thin marlines were then twisted together to make a heavier rope.

Because black students were discriminated against in the public schools of Boston, Primus Hall ran a school for African American students in his home on West Cedar and Revere Streets. His two teachers, both Harvard students, instructed the students on reading, writing, arithmetic, and English grammar. He lived with his father, Prince Hall, who also worked to improve educational opportunities for the African American community on Beacon Hill. It was expensive to run a private school, and students paid twelve and a half cents in tuition each week. When the African Meeting House was built, it housed Primus’ school, and also included a Sunday school for students who could not afford the tuition or who had to work weekdays to support their families.

Because black students were discriminated against in the public schools of Boston, Primus Hall ran a school for African American students in his home on West Cedar and Revere Streets. His two teachers, both Harvard students, instructed the students on reading, writing, arithmetic, and English grammar. He lived with his father, Prince Hall, who also worked to improve educational opportunities for the African American community on Beacon Hill. It was expensive to run a private school, and students paid twelve and a half cents in tuition each week. When the African Meeting House was built, it housed Primus’ school, and also included a Sunday school for students who could not afford the tuition or who had to work weekdays to support their families.

Lucretia Pope was a servant in the home of a wealthy merchant named Nathan Appleton, and a trusted member of the family’s staff. She would have a very long and busy day, starting work before her employers woke up, lighting fires in the fireplaces and bringing breakfast upstairs. During the day she had a variety of tasks – cleaning fireplaces of ash, sweeping carpets, making beds, and serving supper and dinner. She would also have helped take care of the family’s clothes and shoes, washed dishes for the cook, and prepared candles for lighting in the evening. A servant was one of the lower-paying jobs, and even others who worked in the same house (the cook, nursemaid, and coachman) would have earned a higher rate of pay.

Lucretia Pope was a servant in the home of a wealthy merchant named Nathan Appleton, and a trusted member of the family’s staff. She would have a very long and busy day, starting work before her employers woke up, lighting fires in the fireplaces and bringing breakfast upstairs. During the day she had a variety of tasks – cleaning fireplaces of ash, sweeping carpets, making beds, and serving supper and dinner. She would also have helped take care of the family’s clothes and shoes, washed dishes for the cook, and prepared candles for lighting in the evening. A servant was one of the lower-paying jobs, and even others who worked in the same house (the cook, nursemaid, and coachman) would have earned a higher rate of pay.

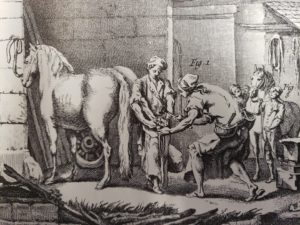

Oliver Davis was a liveryman, stabling horses for regular customers and some for visitors from out of town. Wealthier families owned carriages and horses, and if they didn’t have the space for a carriage house or stable near their home, they paid liverymen like Oliver to take care of their horses. A liveryman’s duties included cleaning each horse’s coat, mane, and tail with brushes and combs, scraping mud or dirt out of their hooves, feeding and watering them twice a day, and using a pitchfork, shovel, and a wheelbarrow to dispose of the horse’s waste before covering the floor with fresh hay or sawdust.

Oliver Davis was a liveryman, stabling horses for regular customers and some for visitors from out of town. Wealthier families owned carriages and horses, and if they didn’t have the space for a carriage house or stable near their home, they paid liverymen like Oliver to take care of their horses. A liveryman’s duties included cleaning each horse’s coat, mane, and tail with brushes and combs, scraping mud or dirt out of their hooves, feeding and watering them twice a day, and using a pitchfork, shovel, and a wheelbarrow to dispose of the horse’s waste before covering the floor with fresh hay or sawdust.

Patriots and Loyalists

A House Divided

By all accounts, Sally and Harrison Gray Otis were politically united, and the Otis family never waivered from the patriot cause. But family politics before, during, and after the American Revolution were often divisive. The portraits of Ruth and James Otis, Jr. (Harrison’s aunt and uncle) that hang in Otis House’s dining room portray a seemingly happily married couple. But in reality, political views between this husband and wife were bitterly divided. James was a lawyer, political activist, legislator, and advocate of views that supported the American Revolution. Ruth, on the other hand, was a staunch Loyalist, which placed her on the opposite end of the political spectrum. A blow to the head during a dispute with a crown official led to James, Jr. becoming increasingly “irascible, unbalanced, and agitated,” until his untimely death in 1789 when he was struck and killed by a bolt of lightening.

Another cause of uneasiness in the Otis family was the growing toryism of Harrison’s maternal grandfather, Harrison Gray. His continual support of the British Crown eventually forced him to flee the Colonies, resulting in exile, permanent separation from friends and family, and the confiscation of his property. Though recovering Tory assets was a delicate business, Harrison persisted out of a sense of loyalty and family duty, and was successful in saving more from his Grandfather’s fortune than did any other agent of a Boston loyalist.

Mercy Otis Warren (Harrison’s aunt, and sister to James Otis, Jr.) was a gifted playwright, poet, and historian who symbolized and promoted the ideas and principles upon which the United States was established. Her most seminal work, History of the Rise, Progress and Termination of the American Revolution, was one of the first comprehensive histories of America’s fight for independence.

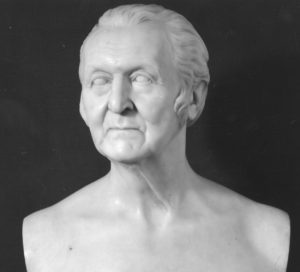

Otis in Politics

Governing in a New Nation

As few families had played a more important part in the Revolution than the Otises, it seems inevitable that Harrison Gray Otis would have a lifelong political career as lawyer, Congressman, Senator, and Mayor. Harrison adhered to the Federalist Party, which under the guidance of Alexander Hamilton, would have provided the sound federal financing that would have appealed to his merchant-shipowner clients.

Alien and Sedition Acts

With fears of enemy spies infiltrating American society, the Federalist majority in Congress passed four new laws in June and July 1798, collectively known as the Alien and Sedition Acts. Harrison Gray Otis, as much as any member of the Congress, was responsible for the passing of this controversial legislation.

The Naturalization Act increased residency requirements for U.S. citizenship to fourteen years from five. The Alien Enemies Act permitted the government to arrest and deport all male citizens of an enemy nation in the event of war. The Alien Friends Act allowed the president to deport any non-citizen suspected of plotting against the government, even in peacetime. The Sedition Act took direct aim at those who spoke out against President John Adams or the Federalist-dominated government. By 1802, all of the Alien and Sedition Acts had been repealed or expired, save for the Alien Enemies Act, which Congress amended in 1918 to include women.

Slavery

Harrison Gray Otis held a moral repugnance to slavery, but his conscience was not greatly troubled by the existence of wrongs for which he did not feel responsible. In both 1798 and 1819, legislation was introduced that included the prohibition of slavery. On both accounts Otis voted with the majority to defeat the bills, twice evading an opportunity to curtail the advance of slavery. Only a year later in 1820 his vote against the Maine-Missouri Bill (The Missouri Compromise), allowing Missouri to enter the Union as slave state and Maine as a free state, shows a reversal in his thinking about the fast-growing nation’s “peculiar institution.”

The Hartford Convention

The official objectives of the Hartford Convention of 1814 were to draft constitutional amendments to protect New England interests, and an agreement with the Federal Government to let the states conduct their own defense during the War of 1812. As the convention finished its business, dispatches were already on their way from Britain containing the peace terms that had been agreed to in the Treaty of Ghent, ending the war, and thus negating the power of the ultimatums contained in the convention’s report. The secrecy of the Hartford proceedings contributed to discrediting the convention, and its unpopularity was a factor in the demise of the Federalist Party.