Otis House

Otis House

Restoration and Preservation

A Continuing Process

In 1916, The Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities (now Historic New England) purchased the house to serve as its headquarters, and restoration of the house was begun. The process was interrupted when Otis House received a demolition notice in 1925 resulting from the City of Boston’s intent to widen Cambridge Street. The house was lifted off its foundation, rolled back forrty two feet, and was attached to the nineteenth century row houses behind it.

In the early 1970s, pioneering work in chemical paint analysis was completed, which led to surprising discoveries about Federal era tastes. In addition, fragments of original wallpaper were used to create reproductions, and with period furniture and finishing touches added using inventories or paintings from similar Federal era homes as a reference, most of the house now appears as it might have looked when Sally and Harrison Otis lived here.

Otis House is Purchased

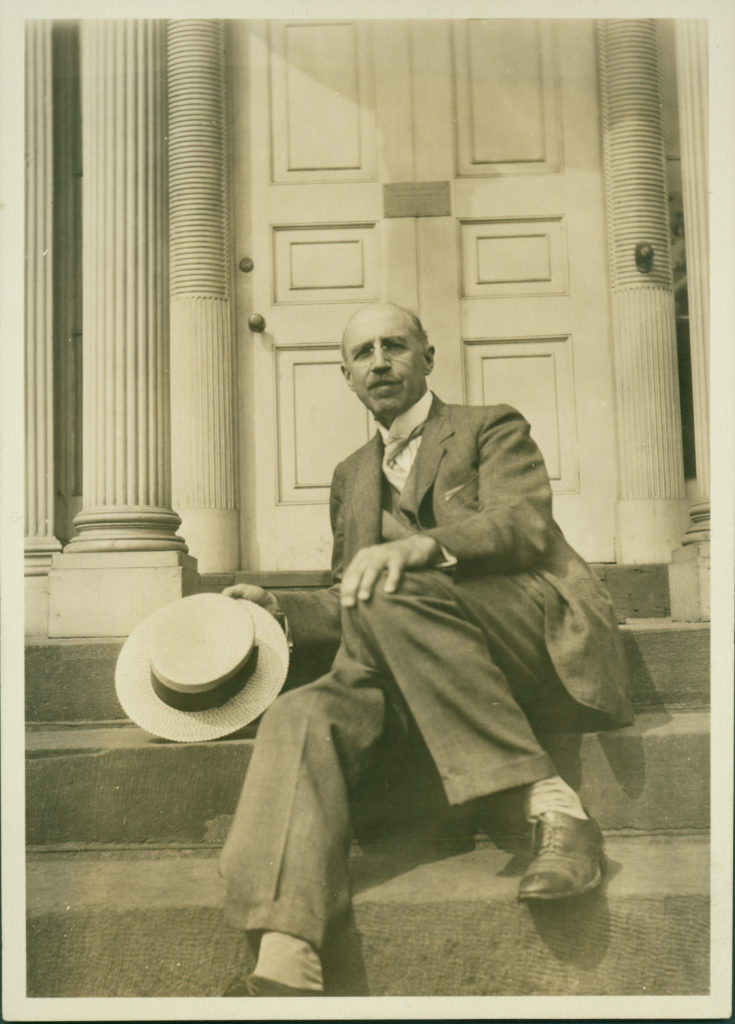

"...a splendid chance to secure another building not much inferior in beauty and even more prominently identified with the city's past." - William Sumner Appleton

In early 1916, founder William Sumner Appleton identified Otis House as a building worth saving and a suitable headquarters and museum for his fledgling preservation organization. In reaction to the increasing diversity of Boston’s population, people of Appleton’s class and lineage began to feel the need to preserve symbols of their heritage. By the time Appleton became interested in acquiring the house, it was in the process of being transferred to the Benoth Israel Sheltering Home for Jewish Women. A friend of Appleton’s interceded and persuaded the organization to sell him the property at a purchase price of $26,000.

Removing the Shops

Last Vestiges of the Nineteenth Century

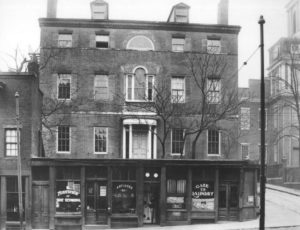

When Historic New England acquired the building, there was still a row of shops on 954 square feet of land between the Otis property and Cambridge Street. Housing a cobbler, a barber, a plumber, and a laundry, their removal did not occur until 1925 in anticipation of the widening of Cambridge Street.

Moving a House

Forty Two Feet and Eleven Inches

When it became clear in 1924 that the City of Boston would proceed with plans to widen cobblestoned and narrow Cambridge Street into a one hundred foot wide thoroughfare, and that the new street would transect the front rooms of the Otis House, SPNEA (now Historic New England) made plans to demolish the shops and move the Otis House back. In 1925, under the direction of founder William Sumner Appleton, Otis House was moved back forty two feet, eleven inches and lowered two feet, nine inches.

Restoring the Parlor

Wallpaper, Carpet, and Paint

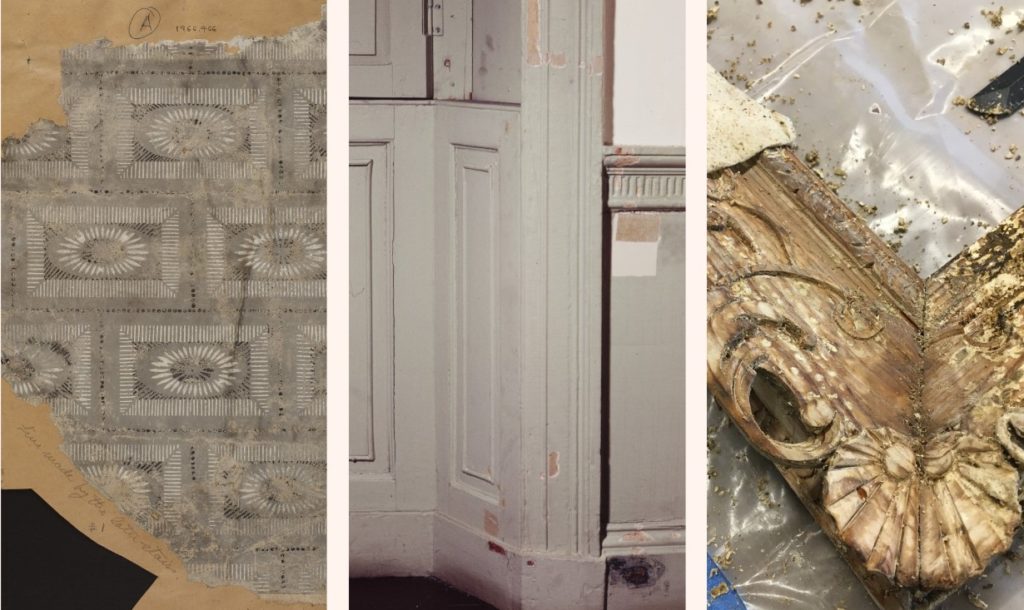

Wallpaper

In the 1916 examination of the Otis House parlor, no Federal era wallpaper remains were found on the walls. For both the parlor or dining room, curators chose to use plain papers with wallpaper borders. Rooms decorated with solid colored wallpaper, called “plain papers”, and embellished with a wide variety of colorful borders were fashionable in the period when Otis House was built. The border in this room is a reproduction of a paper from Montpeiler, the home of Revolutionary War hero, Henry Knox, in Thomaston, Maine. This was a logical choice as Knox was a contemporary of Otis and his house was likely designed by Charles Bulfinch, in 1794. This particular French paper was titled “Scenes from Pompeii”. The discovery and excavation of Roman ruins at Herculaneum and Pompeii beginning in 1738 were made fashionable in England through the designs of the architect Robert Adam and influenced American Neoclassical style. The bright yellow paper set off the bold border and created a striking visual effect in concert with the paint and wall-to-wall carpet.

Carpet

Removal of Victorian carpets in this room revealed unfinished pine boards commonly used under wall-to-wall carpeting. In the Federal era, urban households, especially wealthy ones like the Otises, were likely to possess carpets. By 1790, classically inspired carpets had become popular and this reproduction carpet imitates a Roman tile floor.

Paint

Determining the original paint colors for the room required scientific analysis and involved taking samples from areas where the paint was thickest and then analyzing them chemically and microscopically. Most rooms in the house were painted with variations of a light bluish-green color (note the trim and wall below the chair rail in the picture above) with detail picked out in white.

Hiding in Plain Sight

Conservation in ActionIf Walls Could Talk

What Lies Beneath

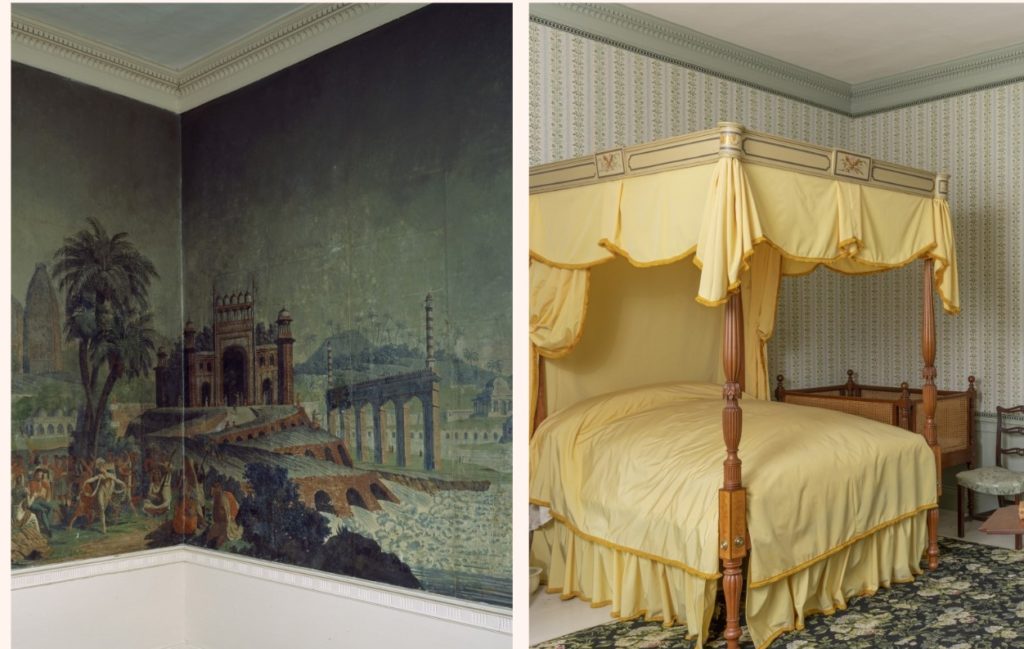

In the 1960s, Sally Otis’s bedchamber was the office of Historic New England president and noted historian Abbott Lowell Cummings. During this period, Historic New England installed a salvaged wallpaper showing idealized views of the Pacific Islands as described by explorer Captain James Cook.

Years later, In order to show a more accurate Otis-era bedchamber, Historic New England covered the scenic wallpaper with a protective wall material and covered it in reproduction wallpaper based on a sample that had been found in the Otis House. This allowed for the preservation of the scenic wallpaper in situ.

Today, lifting the bed hangings at the head of the bed reveals that the scenic wallpaper is still very much intact.