Otis House

Otis House

Time Changes Everything

Otis House is more than simply the last free-standing home in Boston’s West End. It tells the story of dramatic change in the city over hundreds of years and illustrates a shift in demographics, culture, lifestyle, architecture, and topography.

The land that is today’s Boston was once home to the area’s indigenous Massachuset tribe and the village they called Shawmut. It was almost totally surrounded by water and connected to the mainland only by a narrow “neck.” With the arrival of Europeans in 1600s, the town’s prosperity became focused on maritime trade, and the population settled along the harbor on the east and north sides of the peninsula, leaving the west side, bordered by the Charles River and Back Bay, largely undeveloped. By the 1780s, as Boston continued to grow, most of the population still lived along the harbor (indicated on the map in red), with the west end of the city sparsely populated except for industries such as tidal mills and ropeworks. Boston Common remained communal land and above it stood the three hills known as the “Tri-mountain,” the tallest being Beacon Hill.

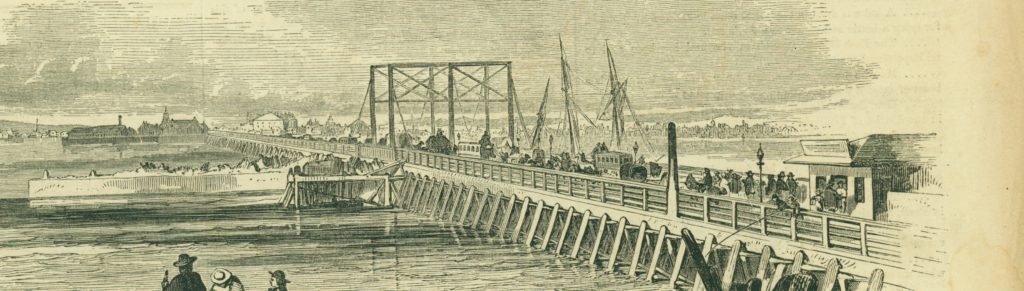

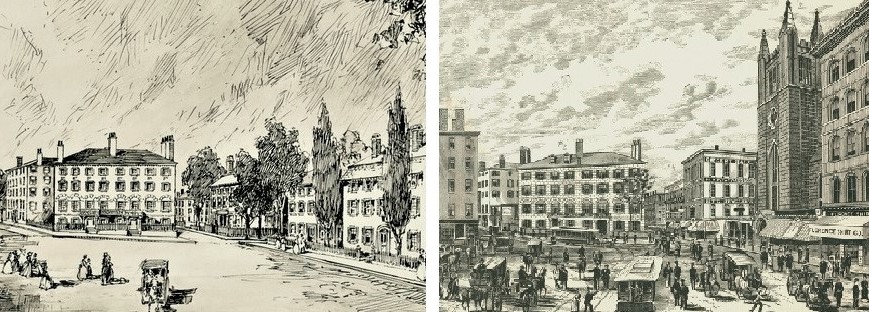

At the northern foot of the Tri-Mountain stood Bowdoin Square, a fashionable neighborhood consisting of large houses owned by Boston’s well-to-do. As the place where their parents’ generation had settled, it was a logical choice for Harrison and Sally Otis to build their new home in 1796. But change came quickly with the building of the West Boston Bridge (now the Longfellow Bridge) connecting Cambridge to Boston. What was originally a quiet, residential road that dead-ended at the river was renamed Cambridge Street and soon became a busy thoroughfare that would drastically change the character of Bowdoin Square.

As traffic along Cambridge Street increased, Bowdoin Square developed into a commercial area. Those who once prized the peaceful location, including the Otises, abandoned it for the new elite neighborhood being developed on the south slope of Beacon Hill overlooking Boston Common. With the flight of wealthy Bostonians, most of the Bowdoin Square’s mansions were torn down and replaced by storefronts, theaters, and churches, or repurposed into hotels, boarding houses, or businesses.

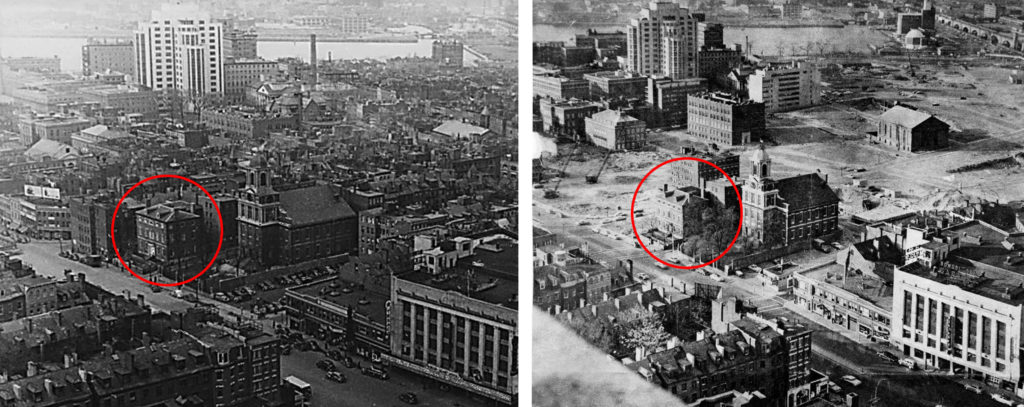

Otis House survived because it was originally built far back from the road. Shortly after the Otises left, the land in front of the house was sold as a separate parcel and developed as storefronts. During the century that followed, the house stood quietly and relative untouched behind the busy stores on Cambridge Street. In 1916, Historic New England purchased Otis House to become its Boston headquarters and museum. Nine years later, the house was saved from demolition when the city’s plan to widen Cambridge Street called for its removal. Historic New England lifted the house and rolled it back more than forty feet. The storefronts were demolished by the city and Otis House once again had an unobstructed view of Cambridge Street.

As the century progressed, the West End continued to become a densely populated working class neighborhood, home to thousands of Jewish, Irish, Italian, and Polish immigrants, joining an already-established African American community. In the 1950’s and 60’s, however, most of the buildings were demolished and the residents displaced during an aggressive urban renewal campaign.

Today, Otis House provides a historic canvas for telling the story of the now-vanished residential neighborhoods of Bowdoin Square and the Old West End. But it also keeps alive the stories of the multitude of people who have, over time, called West Boston their home and illustrates the inevitable change of a modern-day city that continues to grow and evolve.