Otis House

Otis House

Boarding House Chamber

"Like a Large Family"

Genteel boarding houses, like the Otis House in the mid-nineteenth century, relied on reputation by being selective about their clientele and providing a comfortable, middle class home-like setting. Established and stable boarders could expect to live in sizable, well-kept rooms furnished with their own and/or “house furniture,” to sit down to three home cooked meals per day in the dining room, and to entertain their guests in a well-appointed communal parlor on the first floor. For many, these boarding houses were like a large family, providing the rituals of home.

From 1854 -1868, the Otis House was reunited in single family ownership. Four unmarried sisters, Lavina, Maria, Eliza, and Aroline Williams rented the house from the owner to use as a boarding house – an occupation deemed respectable for unmarried women at the time. Adapting an old home to become a boarding house did not require significant alterations, but many boarding house keepers did partition larger rooms.

By the early 20th century, the third floor of Otis House, had been divided into 16 rooms and 5 closets and it was clear that the house had transitioned from a boarding house into a lodging house, the main difference being that lodging houses let rooms only, and did not provide meals or common areas for socializing.

Who Were the Boarders?

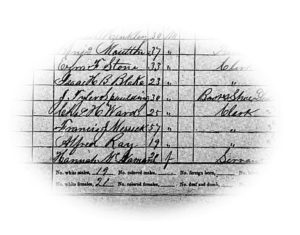

Boarders at Otis House

A snapshot of boarders who lived in the house during the period of WIlliams sisters operation of the boarding house (1854-1868) fall into several categories. From year-to-year the boarding house was occupied by several married couples, usually in their forties, occasionally with a child, and single men, a few middle-aged and the rest in their twenties. The men were mostly employed in white collar or professional occupations; they were naval officers, physicians, editors, news reporters, shoe and boot dealers, merchants, salesmen, and clerks. These include:

George Punchard (1806-1880) and wife Williamine (1810-1876) lived with the sisters throughout their times are boarding house keepers. George Punchard attended Dartmouth College and Andover seminary and was a founder of Boston’s Daily Evening Traveller.

Francis Merrick (1799-1871) was raised in Concord, Mass. A clerk for most of his life, he was employed in the Naval Storekeepers Office at the Boston Navy Yard in Charlestown. Upon his death in 1868, he left $1,100 from his relatively modest estate to the Williams sisters.

Henry Knox Thatcher(1806-1880) and Susan (Croswell) Thatcher (c. 1816-1882); Susan Emerson Thatcher (c. 1852-1941). Henry Thatcher, grandson of revolutionary war hero Henry Knox, was a career naval officer who was likely at sea for most of the time his family was at Otis House. Susan Thatcher and their adopted daughter Susan boarded with the WIlliams’ from 1857 -1859 and again between 1863-1868. Young Susan recalled occupying the parlor and office chambers as a suite with her mother.

It appears the Williams sisters themselves lived in the rear ell of the house and were assisted in their work by several servants. By the time of the sisters retirement in 1868 they had generated sufficient income to invest it and acquire a brick town house just around the corner from Otis House on Chambers Street, two of their long-time boarders, a couple, and their only single female border moved with them.

Life in the Boarding House

Eating, Sleeping, and Bathing

The boarding house retained several public spaces shared by all the boarders including a parlor and dining room. The Otis boarding house chamber was used for sleeping and as a sitting room, and as there was no separate bathroom and running water available to the boarders, personal activities such as bathing and shaving would have taken place here.

The boarding house chamber is furnished with a hat bath, a portable tin tub featuring a seat and drain, which looks like an upside down hat. A toilet table next to the window contains a wash basin, pitchers, shaving supplies, and even a chamber pot that could be neatly tucked away when not in use.

A Home Away From Home

The Rise and Fall of the Boarding House

By the middle of the nineteenth century, few Americans lived only with relatives throughout their lives; many people had boarders in their own homes, boarded with other people’s families, or lived in boarding houses. The rise in popularity of the boarding and lodging house was also fueled by immigration, the solution to a longstanding labor shortage. Arriving without places to live and with few household goods, newly-arrived immigrants often crowded into rooms, living in tenement-like conditions.

Boarding arrangements varied from household to household, and being that boarding was one of the only respectable means for women to earn income, most often the drudgery of running such an enterprise, such as making boarding arrangements, laundry, cooking, and cleaning, fell to women. In practice women often served as surrogate mothers, wives, and sisters for their borders, creating a sense of family.

In the later nineteenth century, the number of urban boarding houses declined, while lodging houses increased. Boarding house keepers found they could rent out the dining room and parlor as additional bedrooms and they could dismiss servants required to prepare and serve meals. In addition to paying a cheaper price, lodgers also found a more independent lifestyle; they could dine and socialize wherever and with whomever they chose.

Though people continue to live with friends or family for short periods of time, boarding has largely disappeared from the American lifestyle, and people who share houses and apartments today often simply share real estate.

Row houses, 10-16 Lynde Street

Row houses, 10-16 Lynde Street

Numbers 14-16 are what remains of a series of four row houses on Lynde Street, tucked behind Otis House and currently used as office space for Historic New England and its tenants. Numbers 10-12 were razed when Otis House was moved back as part of a street improvement project. In 1925, the city of Boston began the widening of Cambridge Street, transforming it from a crooked cobblestoned street to a 100 foot wide thoroughfare intended to relieve congestion in the downtown area.

By 1900, 16 Lynde Street had made the transition from boarding to lodging house. The largest number of residents documented at 16 Lynde is twenty six in 1910. The head of the household was a French Canadian family of four. Of the remaining twenty two residents, eight were members of married couples (one of which had an infant). James and Patrick Walsh were probably brothers. One resident was born in Russia, one in English Canada, two in Ireland, and two in Italy.

Above: Numbers 14-16 Lynde Street, before Otis House is moved back but after 10-12 are razed, 1925.